TL;DR: Society improves when many small advances combine into big breakthroughs.

Here's how progress really works, not with a bang, but with a borrow.

It’s called convergence.

It is a strange, quiet kind of phenomenon that doesn’t belong to any industry but pulls from all of them. Once you know what it looks like, you see it everywhere.

It’s a trend that’s all around us. And once you see it, you can’t unsee it. You start noticing it everywhere. In medicine. In tech. In the way your weather app works, or how your newborn niece survived what would’ve been a fatal birth just 30 years ago.

We think the world changes because of geniuses in lab coats. But more often, it changes because someone asked a simple question: What if this thing from over there… could work right here?

Furthermore, it's also why our lives are considerably and measurably better. Not because one field made a giant leap, but because many small advances from different places quietly converged.

In the early 2000s, Dr. Mary Lou Jepsen, known for her work in display technology, worked on improving screens, making them more transparent, thinner, and cheaper. But instead of just focusing on better screens, she had a bigger idea: what if those same technologies could help us look inside the human brain?

She began imagining a new kind of brain scan using the same ideas behind electronics and optics. Something smaller, cheaper, and more portable than the big MRI machines we use in hospitals today. Jepsen wasn’t a doctor, but she asked a powerful question:

“What if this could work over there?”

Jepsen didn't set out to fix medicine. She just followed a thread from one world to another. That's what convergence looks like. It's not a leap, as much as a drift. An intuition. A sideways glance. A hunch.

Many important inventions and discoveries don’t come from one field alone. They happen when different fields—like medicine, technology, engineering, and science—come together, and our lives are better for it.

Let’s look at how convergence has helped shape our world, sometimes in unexpected but life-saving ways.

Weather Forecasts That Actually Work

Back in 1972, farmers in the Midwest had to rely on newspaper forecasts. One-day predictions were only right about 60% of the time. Anything longer was a guess.

Today, your phone gives you seven-day forecasts that are 80–90% accurate.

This huge improvement didn’t happen because weather experts got smarter. It happened because tools from other areas came together. Satellites—originally built to watch Cold War enemies—were used to track weather systems. Supercomputers that used to simulate nuclear explosions were used to model the atmosphere.

Artificial intelligence (AI), trained on weather data, started spotting patterns faster than any human could.

One big example: IBM’s GRAF system uses advanced computing to deliver updates every hour, all around the globe. It’s the first global model that can forecast weather down to just 3 kilometers in resolution—like switching from a blurry photo to HD.

While most systems update every 6–12 hours, GRAF delivers new forecasts hourly, giving people more accurate, up-to-the-minute information. Unlike most high-resolution models, which are limited to specific countries, GRAF covers the entire globe.

IBM’s GRAF is a breakthrough weather model made possible by the convergence of defense satellites, AI, supercomputers, crowdsourced smartphone data, and research collaboration, delivering hyper-local, hourly forecasts worldwide.

Here, Cameron Clayton, GM of IBM Watson Media and Weather, explains how the new GRAF model brings hourly, 3 km-resolution forecasts to regions like India helping farmers make smarter daily decisions with more accurate rainfall predictions.

Airplane Tech Made Cars Safer

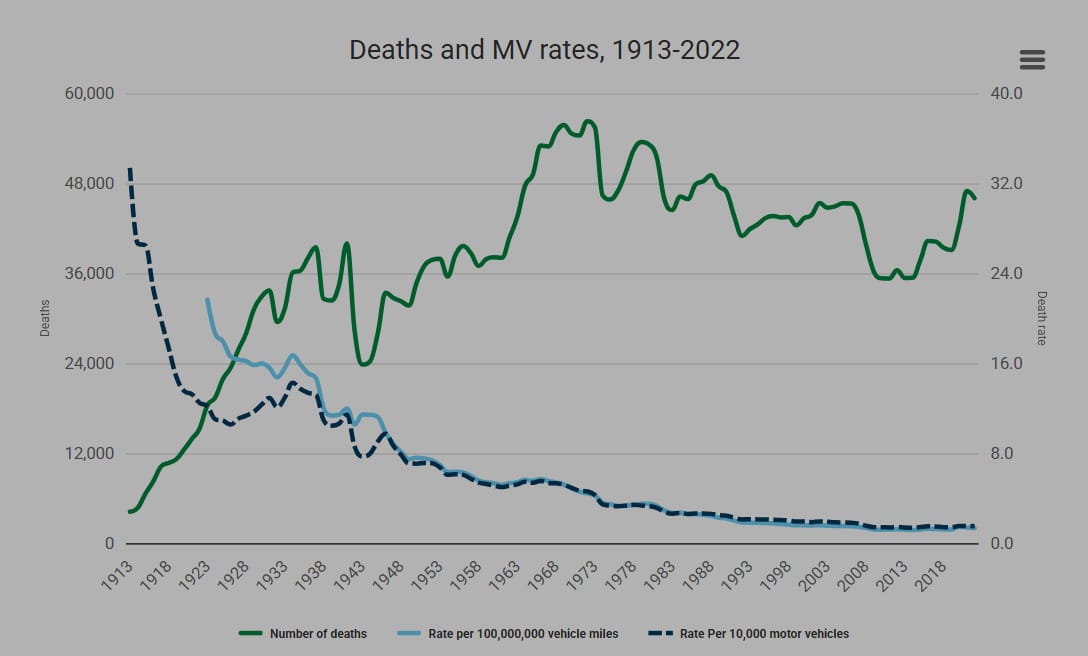

In 1970, about 4.7 people died for every 100 million miles driven on U.S. roads—roughly three times today’s risk. Anti‑lock brakes (ABS) were the first big breakthrough. Engineers had used ABS on jet landing gear in the 1950s to stop wheels from skidding when planes touched down when airplane engineers at Dunlop invented Maxaret, the first anti‑skid brake.

Jump ahead to 1971. Italian engineer Mario Palazzetti built the first fully electronic anti‑lock braking system (ABS) at Fiat’s research center. Bosch bought the patent and soon Mercedes‑Benz began selling cars with ABS in 1978. Car makers added electronic ABS in the early 1980s, giving drivers more control during hard stops, especially on wet or icy roads.

Next came other cockpit ideas: head‑up displays (HUDs) project speed and directions onto the windshield so drivers can keep their eyes forward. The first heads-up displays were developed in the aviation industry in the 1940s. The US military used them to display critical information to pilots during World War II. The HUD was designed to project information such as altitude, airspeed, and other crucial information onto a transparent glass screen in front of the pilot.

This allowed the pilot to keep their eyes on the sky while still being able to monitor their instruments. Aviation heads-up displays served as an example for automobile manufacturers, who saw the prospect of using them to improve road safety by helping drivers be distracted less often because key indicators would be right in their field of vision.

We also have automatic emergency braking (AEB) that uses radar or cameras, similar to aircraft sensors—to hit the brakes if a crash is about to happen. Cars with AEB have 40–50 percent fewer rear‑end crashes than cars without. All vehicles are now supposed to have AEB by 2029.

The payoff shows up in national numbers. U.S. road‑death rates fell from about 5.5 deaths per 100 million miles in 1966 to around 1.3 by 2020—a drop of roughly 70 percent. That's thanks to seat belts, airbags, stronger frames, and these aviation spin‑offs.

How Premature Babies Started Surviving

Before the early 1980s, many babies born very early died because their lungs were missing a “soapy” film called surfactant. Without this film, the tiny air sacs inside their lungs stuck together, and breathing was like trying to blow up a balloon that keeps collapsing. Doctors could save only about 3 or 4 out of every 10 of these babies.

Researchers then proved that surfactant was the missing piece and learned how to make it in the lab. In 1990–1991 hospitals began giving this surfactant to preemie babies through a breathing tube. Deaths from lung failure dropped fast, and by the end of the 1990s around 6–7 out of 10 very‑small preemies were living.

Other high‑tech tools—many first built for the military—also helped. The pulse‑oximeter, a fingertip sensor first tested on World War II pilots, lets nurses track a baby’s oxygen level without drawing blood. Lightweight ventilators and monitors designed for battlefields were adapted for hospital nurseries.

Today, in well‑equipped hospitals, more than 9 out of 10 babies born at 28 weeks of pregnancy or later survive. The smallest, earliest babies still face tougher odds, but surfactant therapy plus modern sensors and gentle ventilation have turned pre‑term birth from often fatal into usually treatable. A mix of chemistry, aerospace, and medicine made this possible.

Read More:

Cancer Treatments Powered by Tech

In the early 1980s, only about half of people diagnosed with cancer were still alive five years later. Scientists then finished the Human Genome Project in 2003 and produced the first full “instruction manual” for human DNA. That map helped doctors design drugs that strike the exact gene mistakes inside a tumour, pushing five‑year survival into the low‑60 percent range during the 2000s.

Next, huge gains in computer power sped things up. Cloud systems—originally built to run shopping sites—now sift through mountains of genetic and scan data in hours.

Artificial‑intelligence programs, like the ones that spot credit‑card fraud, search for hidden cancer clues and match patients to the best treatment.

By the late 2010s, fast DNA‑sequencing machines (from companies such as Illumina) and early tests of the gene‑editing tool CRISPR pushed overall U.S. five‑year survival close to 70 percent. Some cancers do even better: childhood acute lymphoblastic leukaemia now tops 90 percent. CRISPR is still in early trials, so it hasn’t moved the big survival numbers yet, but the trend is clear—better data and smarter tools keep saving more lives.

Read More:

From Game Controllers to the Operating Room — Surgeons With Video Game Skill Appear To Perform Better

In the 1990s, a handful of researchers proposed that playing video games could sharpen surgeons’ hand–eye coordination, but many experts dismissed the idea as a gimmick meant for kids, not doctors.

Around the same time, hospitals began adopting the first robotic surgery platforms—such as the da Vinci system, cleared by the FDA in 2000—but these robots relied on custom hand consoles, not off‑the‑shelf gamepads.

Fast‑forward to August 2024: engineers at ETH Zurich and the Chinese University of Hong Kong performed a tele‑operated magnetic endoscopy on a live pig 9,300 km away, steering the probe with a PlayStation Move joystick. The procedure showed that a device once written off as “too childish” can guide delicate surgical tools with millimeter precision.

The lesson is clear—sometimes the technology is ready long before mindsets catch up.

Why We Don’t See It—and Why It’s So Important

Convergence doesn’t come with headlines. It hides in the overlap of industries. We often miss it because we reward vertical mastery, not lateral insight, when someone notices a pattern or asks a new kind of question.

They borrow a tool, repurpose a theory, and ask, " What if this could work over there?"

Tangible progress and breakthroughs usually occur when someone connects two or more very different things.

Why do we miss convergence?

It doesn’t fit neatly into one category.

It looks messy.

It comes from unexpected directions.

Because institutions reward expertise, not exploration.

Because we rarely ask: what else could this be used for?

Start Connecting More Dots: The Muscle of Convergence

If you want to reap the benefits of convergence, start by giving yourself permission to look outside your usual lane. Don’t just go deeper into what you already know—go wider. Explore ideas from other industries.

Talk to people in completely different fields. Read or watch something that seems unrelated to your work. Then ask yourself: "Could this be useful here?"

You don’t need to be an expert in everything. You need to notice patterns, ask new kinds of questions, and connect ideas that don’t usually go together. Try small experiments. Take one tool or insight from elsewhere and test it in your world.

Breakthroughs rarely come from staying in your box. They come from crossing boundaries. The more often you reach beyond your usual space, the more likely you are to find the next big idea hiding in plain sight.

Progress isn't a straight line. It zigs. It zags. It loops. It wanders. It’s a constellation, or a puzzle being pieced together.

And your life is better, not because one thing got better, but because many other things were happening simultaneously. That’s convergence. That’s how we got here. And that’s how we’ll get to what’s next.